The following blog is by Carl Richards originally published in The New York Times’ Blog.

Back in 2008, a friend of mine left for a two-week trek in Nepal. While he was gone, the entire financial world exploded.

Merrill Lynch was sold to Bank of America. Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy protection. A.I.G. received an $85 billion loan from the Federal Reserve to avoid bankruptcy.

But here’s the interesting part: he didn’t know anything happened because he didn’t have any connection to the outside world. Although recently retired from the investment industry, my friend would have been glued to his computer. But he had no idea what was going on.

Think about that for a minute. I remember those days. I remember waiting up to see how markets opened in Japan. I remember being so worried that I didn’t sleep for days. And I remember another friend who called me from a cruise ship to ask if things were O.K. He said that many other passengers got off at the first port and flew home to deal with what was happening in the market.

My friend in Nepal missed it all, and it didn’t make one bit of difference. He was actually better off. All my worrying didn’t change one thing.

In fact, my friend said that when he got back and eventually heard the news, something became crystal clear. He knew exactly what was going to happen for the rest of his life: the markets were either going to move up and then down, and then up and down again — and then he would die. Or, they would go down and up and down and up — and then he would die.

In either scenario, he was still dead. And no amount of obsessing over the stock market would change that.

This idea of being unconnected for a few weeks reminded me of Warren Buffett’s statement: “Benign neglect, bordering on sloth, remains the hallmark of our investment process.”

But it’s still so hard to ignore the market because we’re so connected. We seem to be obsessed with economic news. I’m not sure when exactly it happened, but sometime in the 1990s investing became America’s favorite spectator sport. I knew there was a problem while sitting in my dentist’s office and seeing CNBC on the TV in the lobby. It’s only become more difficult to avoid, now that everyone has a smartphone.

But knowing doesn’t help. And much of the time, it actually hurts. Aside from the tendency to trade too much when we’re following every market move, there’s also the issue of our happiness. It doesn’t feel good when our investments go down, even if it’s just for one day.

We have an aversion to loss. In other words, you’re likely to feel the pain of loss far more acutely than the joy of an investment gain. We feel twice as bad losing money as we do making money. And yet, knowing this, we continue to do things that will cause us pain.

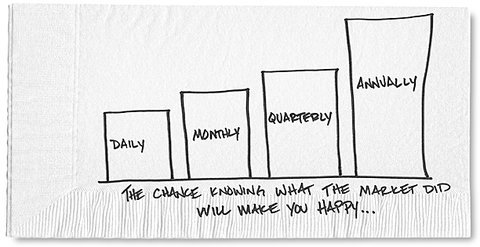

Since many of us use the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index as a proxy for the market, let’s take a look at the period from 1950 to 2012 to see how often we’re likely to feel positive, based on how often we check our investments:

- If you checked daily, it would be positive 52.8 percent of the time.

- If you checked monthly, it would be positive 63.1 percent of the time.

- If you checked quarterly, it would be positive 68.7 percent of the time.

- If you checked annually, it would be positive 77.8 percent of the time.

So here’s the thing to ask yourself. Other than upsetting yourself half of the time, what good is it doing you to look anyway? Maybe we should all invest as if we’re going on a 12-month trek in Nepal!

So along with your do-nothing streak, let’s see how long you can go without looking at your investments (assuming you’re in a low-cost, diversified portfolio, of course). I think you’ll discover that it makes you happier, keeps you from doing something stupid and helps you become a more successful investor.

About the author: For the last 15 years, Carl Richards has been writing and drawing about the relationship between emotion and money to help make investing easier for the average investor. His first book, “Behavior Gap: Simple Ways to Stop Doing Dumb Things With Money,” was published by Penguin/Portfolio in January 2012. Carl is the director of investor education at BAM Advisor Services. His sketches can be found at behaviorgap.com, and he also contributes to the New York Times Bucks Blog and Morningstar Advisor. You can now buy – “The Behavior Gap” by Carl Richard’s at AMAZON.

0 Comments