The following blog is by Carl Richards originally published in The New York Times’ Blog.

I recently got a new smartphone. In the setup process, I was presented with all sorts of options. Selecting a language was pretty easy, but I had to think harder about some of the other ones. Did I want the phone to use my location? Did I want to share data anonymously? Did I want to log in with an existing account or did I need to set up a new one?

All these options, all these decisions, and all I wanted to do was make a phone call.

Turns out, I’m not alone. Only half of all cellphone users download apps, and a much smaller group (5 percent) do things like “show codes for movie admission or to show an airline boarding pass.”

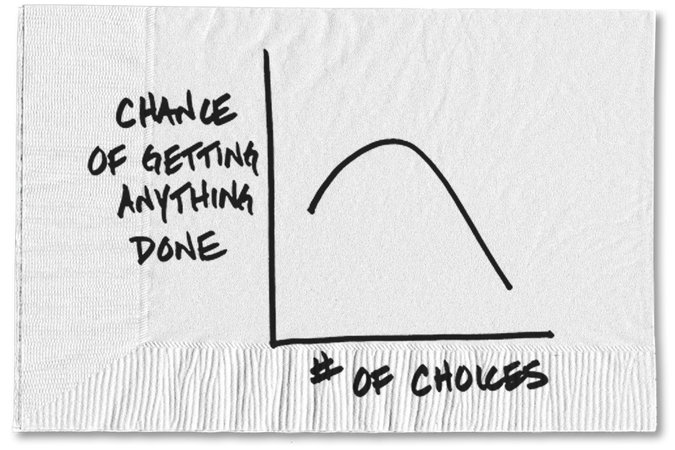

More options don’t equal better choices. Barry Schwartz captured this conflict perfectly in his book “The Paradox of Choice”:

“When people have no choice, life is almost unbearable … But as the number of choices keeps growing, negative aspects of having a multitude of options begin to appear … the negatives escalate until we become overloaded. At this point, choice no longer liberates, but debilitates. It might even be said to tyrannize.”

The worst part of that tyranny shows up when we decide to do nothing in the face of overwhelming options. Instead of being O.K. with good enough, we take a look at our options and then convince ourselves that if we keep looking, we’ll find something even better. However, looking for the best often comes at the expense of making any progress at all.

Investing comes with so many choices today. At the beginning of 2013, there were more than 7,000 mutual funds to choose from. The number of exchange-traded funds crossed 1,500 in 2013. When you add all the share classes, these funds are available with close to 25,000 options, and that’s just a start.

Realistically, you could spend your entire life looking for the perfect investment, or you could use a broadly diversified, low-cost index fund like one of the Vanguard LifeStrategy Funds and call it good. Sure, there might be a better way to invest, but doing nothing isn’t one of them. So what’s wrong with just calling it good enough and moving on?

Then there’s the process of buying a house. We could spend months weighing the pros and cons of different houses and different mortgages. But what if we focused on the house that cost the least and still met all of our needs? Then, what if we didn’t debate different types of mortgages but opted for the shortest-term mortgage we could afford? Will we miss out on something? Maybe. On the other hand, if we don’t let all the options distract us, we may actually move in before we turn 80.

Life insurance is another money decision that keeps people awake at night. Do we really need insurance? If so, how much? Should we go with term, variable or whole life? The decision becomes a lot easier when we cut through the clutter and get a quote for $1 million on a 20-year term policy. Long term, we might need something else, but $1 million will help us sleep easier at night, and it’s often good enough.

We could spend the rest of our lives researching an ever-increasing number of choices and searching for perfect, but to what end? We have better things to do. So grab an index card, write down, “It’s good enough,” and put it in your pocket. Then, the next time you’re tempted to research yet another option, pull out the card and remind yourself that doing good enough will usually beat searching for, but never finding, perfection.

About the author: For the last 15 years, Carl Richards has been writing and drawing about the relationship between emotion and money to help make investing easier for the average investor. His first book, “Behavior Gap: Simple Ways to Stop Doing Dumb Things With Money,” was published by Penguin/Portfolio in January 2012. Carl is the director of investor education at BAM Advisor Services. His sketches can be found at behaviorgap.com, and he also contributes to the New York Times Bucks Blog and Morningstar Advisor. You can now buy – “The Behavior Gap” by Carl Richard’s at AMAZON.

0 Comments