The following blog is by Carl Richards originally published in The New York Times’ Blog.

How often do we hear ourselves saying we want more? More freedom, more money, more time. More seems as if it would always be great, until we get it. Then we’re faced with a new set of problems that comes with having more.

My work is location-independent. My wife and I could live anywhere that our budget will allow, and that ends up being a lot of places. Normally having more options is what we want, but this has actually led to a consistent problem that we spend a lot of time discussing.

When we decided we were ready to leave Las Vegas, the options were a bit overwhelming. We started to envy friends who were transferred to a specific city for work, even if the city wasn’t our idea of paradise.

It removed the pain of having all these options. It made things simple. They went where they were told. Instead of considering multiple cities and states, our friends just needed to find the best place to live within one geographic area.

Besides our budget, we didn’t have much else to help narrow our options. The number of options wasn’t making the process easier, just more stressful. Luckily our decision to land in Park City, Utah, has worked out incredibly well. But I’m not looking forward to the day (if it comes) that we decide it’s time to move again.

I was reminded of this “more dilemma” a few weeks ago on my way to an interview. The taxi driver asked me where I was headed. I explained that I was on my way to talk about what advice I’d offer to the next Powerball winner. Barely able to contain his excitement, my driver pulled out his lottery tickets, and while waving them around, talked about how amazing it would be if he won.

Three tickets ended up winning the $448 million jackpot, two in New Jersey and one in Minnesota. I’m pretty sure my taxi driver wasn’t one of them, but our conversation got me thinking about this question: Why do we want to win? Yes, I do know there’s an obvious answer, but the obvious answer hides a few problems.

We say we want more money (who doesn’t?), but it’s surprising to me how few people can explain exactly what they’d do with that money. Oddly enough, not knowing why we want more can create problems.

Think about our constant pursuit of happiness (it is affirmed in the Declaration of Independence). We often define happiness as more money or time, but if we don’t understand why we’re pursuing it, can we really understand the trade-offs involved?

Do we understand that the pursuit may actually cost us the very thing we’re pushing so hard to achieve?

Paul Graham, the co-founder of Y Combinator, has an interesting perspective on this problem. As a successful programmer and venture capitalist, he’s had many opportunities to see this pursuit of more up close and offered this thoughtful insight:

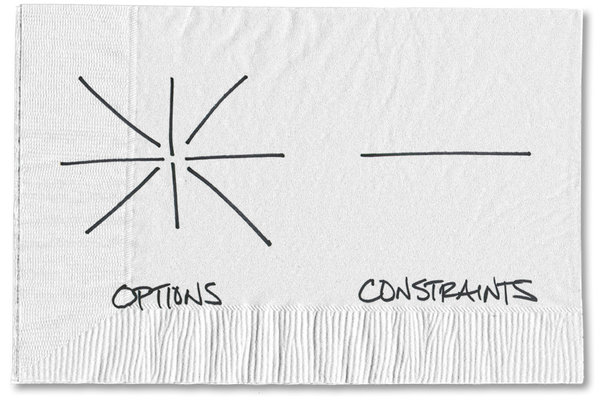

“Most people would say, I’d take that problem. Give me a million dollars and I’ll figure out what to do. But it’s harder than it looks. Constraints give your life shape. Remove them and most people have no idea what to do: look at what happens to those who win lotteries or inherit money. Much as everyone thinks they want financial security, the happiest people are not those who have it, but those who like what they do. So a plan that promises freedom at the expense of knowing what to do with it may not be as good as it seems.”

It may seem counterintuitive, but constraints give us something to use as a framework, a way to help us judge what we do next. Think about what constraints do for investing. Imagine you had more time to focus on your portfolio. What would you do with it?

I suspect you might do something kind of foolish, like trying your hand at being a day trader. After all, you have the time, why not? But if your time is limited, how much more likely are you to behave? How much easier would it be to buy good things and then own them a long time because you don’t have the time to do anything else?

It seems crazy to think about having too much time. Yet I see retirees or entrepreneurs who sold their businesses bouncing off the walls in the first few months of making the transition. They suddenly have all this time on their hands, and freed from the constraints of a daily schedule, they don’t know what to do. More time hasn’t made their lives happier, at least at the beginning, but I suspect many of them thought it would.

Sometimes we become so focused on what we think we should want that we’re blinded to what’s right in front of us. A great example is this classic joke:

A fisherman owns a boat and is running a nice fishing business with it. He meets a venture capitalist who promptly offers to invest in the man’s business.

Fisherman: “Why would I want you to invest?”

V.C.: “Well, with my capital you can buy a second boat and double the size of your business.”

Fisherman: “And why would I want to do that?”

V.C.: “Because eventually you’ll grow your business so large that you’ll end up selling it and making a big wad of cash.”

Fisherman: “You mean, so that I’ll be able to retire down here and buy a boat?”

I’m the first to admit that more freedom, more money and more time can mean good things for people. But the next time you hear yourself saying, “I want more… ,” you’ll most likely be happier with the result if you remind yourself of these three things:

1. More of anything doesn’t always make life easier, and it can make your choices harder.

2. Constraints can give us structure and help us make the most of what we do have.

3. If you’re chasing after more, do yourself a favor and create a plan for what you’ll do if you ever get it.

More without constraints or plans just becomes a burden, one more problem we need to solve. And that seems like the last thing that will make you happy.

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

Correction: August 19, 2013

An earlier version of this article misidentified the American document that refers to the pursuit of happiness. It is the Declaration of Independence, not the Constitution.

About the author: For the last 15 years, Carl Richards has been writing and drawing about the relationship between emotion and money to help make investing easier for the average investor. His first book, “Behavior Gap: Simple Ways to Stop Doing Dumb Things With Money,” was published by Penguin/Portfolio in January 2012. Carl is the director of investor education at BAM Advisor Services. His sketches can be found at behaviorgap.com, and he also contributes to the New York Times Bucks Blog and Morningstar Advisor. You can now buy – “The Behavior Gap” by Carl Richard’s at AMAZON.

0 Comments