The following blog is by Carl Richards originally published in The New York Times’ Blog.

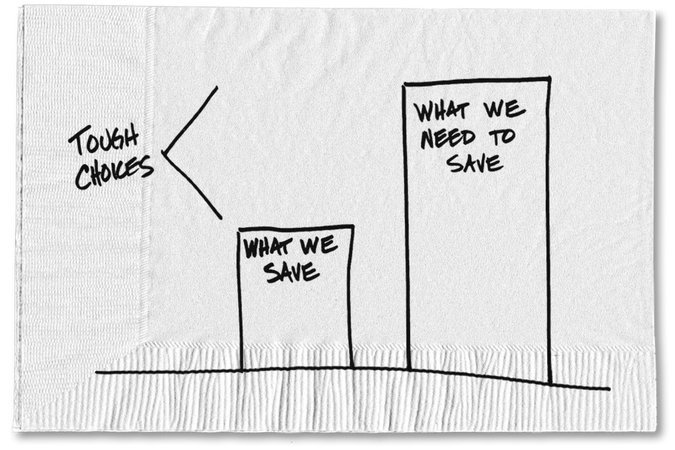

Americans aren’t saving enough.

The numbers appear to back up this claim, which we hear repeatedly. But what I find more interesting is how we react to such statements. I touched on the issue of savings last week, and the responses I’ve heard seem to confirm that it’s a touchy subject.

For the sake of argument, let’s agree the numbers are true and we’re woefully behind on saving. We have some options.

1. We can dismiss it

Not factually, of course, but we can choose to ignore it. We pretend it doesn’t apply to us and never use a calculator to confirm our own savings shortfall.

2. We can delay thinking about it

“There’s time,” we tell ourselves. “We’ll get started … eventually.” Unfortunately, this option feeds into another common mistake. It doesn’t ever really get easier to see our future selves. As a result, we keep putting off tomorrow until the next tomorrow and then the next.

3. We can secretly believe in magic

Through a random chain of events (like winning the lottery, perhaps), we believe the problem will just take care of itself. For comparison, look out West. We’re short on both water and interest in dealing with the issue. Las Vegas, Phoenix and the entire state of California have a critical water problem. But the response is like the modern-day equivalent of expecting a champion to magically appear, slay the dragon and free the princess. And if all else fails, there will always be technology to save the day, right?

4. We can make tough changes

I recognize that some people are literally counting every penny when it comes to keeping a roof over their heads and food on the table. But for the rest of us, we can choose to make the issue personal.

This last option demands asking questions many of us have avoided, including one of my personal favorites. Could we say “no” to something now so we can say “yes” to something later? We know there are people who spend less than us and are just as happy, if not happier. Yet we seem to be satisfied with telling ourselves that it just isn’t possible to cut back — on anything.

When I’ve discussed savings previously, I pointed readers to Mr. Money Mustache and his popular blog. He doesn’t shy away from pulling apart all the reasons we use to justify why we can’t save more. Every excuse, from convenience to safety, gets challenged, and the takeaway is a simple, if uncomfortable, conclusion: Every day we make choices. Some of those choices are driven by circumstances we don’t control, like going to the emergency room with a case of appendicitis. But other choices are just that, choices, which means we have options. How much we save falls into this latter category the vast majority of the time.

Letting ourselves get sucked into the bigger question of whether Americans are saving enough allows us to ignore our personal reality for another day. It’s not about us individually. It’s about all Americans, and surely we’re doing better than most of them.

One useful number in figuring out how well we’re saving is something called the Lifetime Wealth Ratio. This concept was introduced by the budget blogger J. Money on his website, Budgets Are Sexy. To start, take your total net worth and divide it by the total amount of income you’ve earned over your entire life. You can get your total income from your Social Security statement. By adding up the value of your current assets (including all investments and retirement and other savings plus equity in your home), minus your debt, you’ll have your total net worth.

What does the ratio reveal? How much have we really managed to save? Ten percent? Fifty percent? This number represents one of the best ways I’ve seen to close the gap between our past and future selves. If we’re looking at a number less than 10 percent, it’s hard to argue we’re doing everything we can.

But whatever the number, I hope it’s clear that this issue isn’t about anybody else. It is about our individual situation alone. The next time we hear, “Americans aren’t saving enough,” what we really need to know is whether we’re saving enough ourselves.

About the author: For the last 15 years, Carl Richards has been writing and drawing about the relationship between emotion and money to help make investing easier for the average investor. His first book, “Behavior Gap: Simple Ways to Stop Doing Dumb Things With Money,” was published by Penguin/Portfolio in January 2012. Carl is the director of investor education at BAM Advisor Services. His sketches can be found at behaviorgap.com, and he also contributes to the New York Times Bucks Blog and Morningstar Advisor. You can now buy – “The Behavior Gap” by Carl Richard’s at AMAZON.

Social media makes it even harder to resist spending. Friends & family posting pictures of their vacation on facebook doesn’t help. Americans make celebrities of people who have no talent to speak of, following their every move. Not my idea of a role models.