The following blog is by Carl Richards originally published in The New York Times’ Blog.

Some of us really like the status quo. Even when we have a better alternative, many of us are content to keep on doing what we’re doing.

I think about this every time my wife and I swap cars. Depending on who is running what errands that day, we’ll switch between our big car and our little car.

Every time we change, my wife has this habit. It’s a very good habit, but it’s the exact opposite of what I do. Before she backs out of the garage, she adjusts everything. The seat slides closer and the mirrors get moved. She even fiddles with the height of the seatbelt. Only then does she head down the road.

I, on the other hand, just get into the car and slide back the seat (because I wouldn’t fit otherwise). But everything else I leave alone. Things are great — until I try to look in any of the mirrors. Because the mirrors are still where my wife left them, I can only see out of them if I slouch down and move back and forth.

I’ve been known to do this for an entire day. But sometimes, I’ve been in this ridiculous position sitting at a stop light, and I’ve thought to my slouched-down self, “Just reach up and adjust the mirror.” It takes less than 10 seconds, and my whole day gets a lot more comfortable.

So why don’t I skip the slouching and adjust my mirrors every time we swap cars? I don’t think about it. You could call me lazy, but I call it status quo bias. I didn’t just make that up. Researchers have known about this quirk for a while. Even in the face of what would clearly be a better alternative, humans have a tendency to leave things the same.

The “why” behind this bias fascinates me. In 1988, William Samuelson and Richard Zeckhauser gave a name to our habit of disproportionately sticking with the status quo. The bias was so obvious that researchers could see it in a simple, multiple-choice questionnaire that study participants completed. We’re talking about random, “what-if” questions that would have zero personal impact on a participant, like, “How would you allocate the budget for the National Highway Safety Commission?” People still showed a strong preference for the choice identified as the status quo.

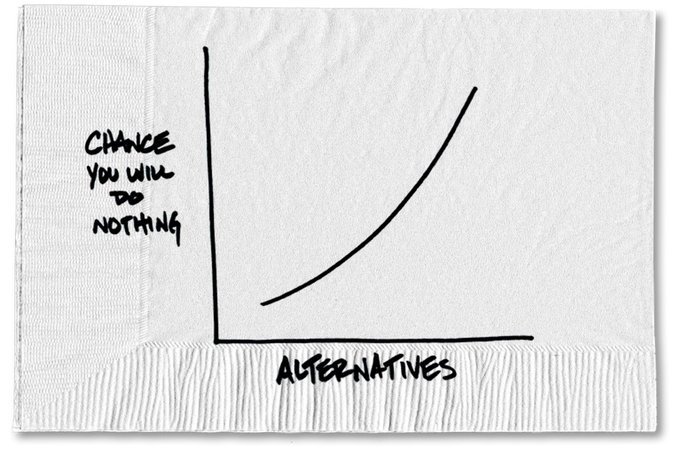

There has been a lot of work done in this area since, including an interesting study by Alexander Kempf and Stefan Ruenzi. Using the mutual fund industry, they found two things:

■People will stick with a mutual fund that’s familiar even when there’s a better option available.

■The bias became “more severe” when the number of fund choices increases. In fact, when the number of choices jumped from less than 25 to more than 100, the observed bias was three times greater.

This research probably confirms what you’ve felt for years. We don’t like that feeling of complexity. So we ignore the alternatives and stick with what we know.

It may be as complicated as picking a mutual fund or as routine as grabbing a new tube of toothpaste at the grocery store. Whatever the choice, if we feel too overwhelmed, we put off making a decision. And avoiding any decision is the ultimate form of sticking with the status quo.

One powerful way to deal with the bias is the reversal test proposed by Nick Bostrom and Toby Ord. Imagine you inherit a family cabin in the mountains. You haven’t spent time there in years, and your family isn’t really interested in weekends at the cabin. Another family member offers to buy the cabin for $100,000. But you hesitate. You’ve got these great memories, and sticking with the status quo lets you keep it.

Reverse the choice. Now you have $100,000 in the bank. Would you use that money to buy the family cabin?

The goal isn’t to change things for the sake of change, but to give ourselves room and time to review our options without getting stuck in the status quo. We need to give ourselves permission to change if there’s a better choice.

In other words, it would make a lot of sense for me to just reach up and adjust the rearview mirror.

About the author: For the last 15 years, Carl Richards has been writing and drawing about the relationship between emotion and money to help make investing easier for the average investor. His first book, “Behavior Gap: Simple Ways to Stop Doing Dumb Things With Money,” was published by Penguin/Portfolio in January 2012. Carl is the director of investor education at BAM Advisor Services. His sketches can be found at behaviorgap.com, and he also contributes to the New York Times Bucks Blog and Morningstar Advisor. You can now buy – “The Behavior Gap” by Carl Richard’s at AMAZON.

0 Comments