There are two types of experts in the world: real experts, and fake ones.

The real experts are the people who spend many years refining their knowledge and skill set in a particular area and become masters of pattern recognition. But all too often, they end up toiling away in relative obscurity and poverty, neither maximizing their opportunity for impact nor earning the money they deserve.

This makes me sad. Real experts deserve so much more, and they could make so much more of a difference in the world if they could just figure out how to be heard above the clamor of …

Fake experts. This group makes me mad. You know the type. These are people, as the writer Sean Blanda put it in describing certain other writers, whose “interest is not in making the reader’s life any better, it is in building their own profile as some kind of influencer or thought leader.”

Your inbox is probably full of fake experts and their garbage. They are people like the speaker I heard at a conference who claimed that all you had to do to be an expert was raise your hand. That’s not expertise. It’s snake oil.

I didn’t realize that there was a way to fix this problem. In fact, I didn’t even know exactly what the problem was until I read David Baker’s new book, “The Business of Expertise.”

One of Mr. Baker’s key insights is the decoupling of time and results. Experts can often see a problem and quickly provide a solution, and that makes them valuable, even though it appears easy and quick in each instance.

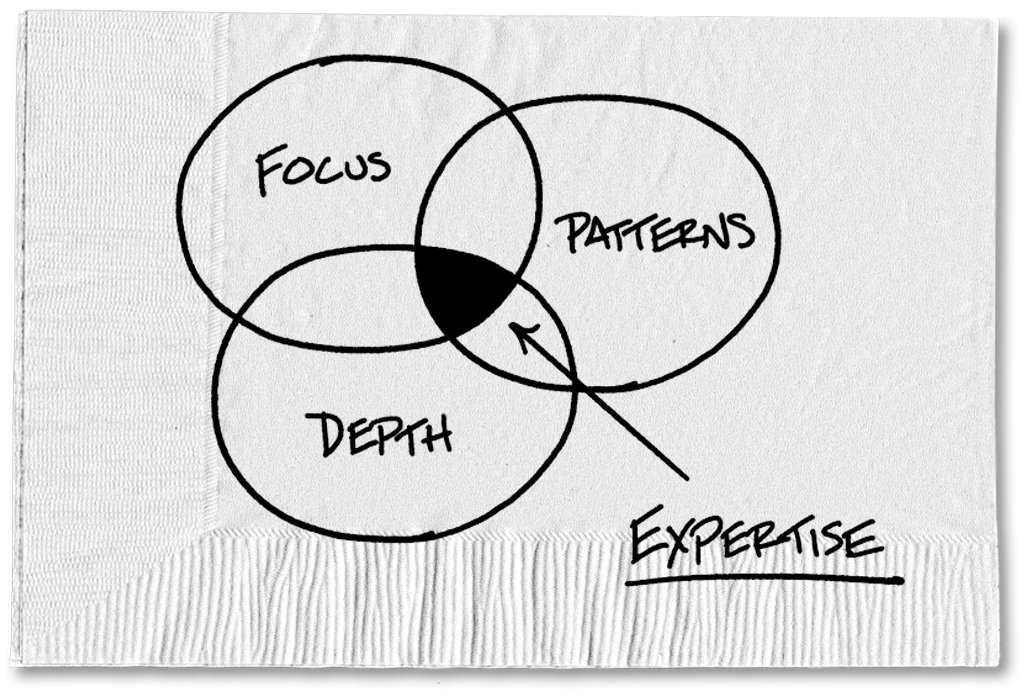

In fact, it’s not easy at all. You become an expert through repeated exposure to similar patterns. After doing hundreds of financial planning meetings with new or potential clients, I started noticing those patterns. Eventually, I got to the point where in the first 10 minutes of asking about people’s goals, I often knew exactly where they were headed, what sort of risk they might be comfortable with and where the challenges might be.

He handed the lady a $100 invoice, and she wanted to know why 10 minutes of his time required such a big payment. “Oh,” said the carpenter. “I forgot to itemize that.”

Nail: $1.00

Knowing where to pound nail: $99.00

She paid. And Mr. Baker taught me much more about the value of knowing exactly where to pound.

The above blog is by Carl Richards originally published in The New York Times’ Blog.

About the Author: Carl Richards, a certified financial planner, is the author of “The Behavior Gap” and “The One-Page Financial Plan.” His sketches and essays appear weekly in the New York Times.

0 Comments