The following blog is by Carl Richards originally published in The New York Times’ Blog.

How many spreadsheets do you have on your computer? I bet a lot of you have at least one or two. There’s probably a budget spreadsheet showing how much you’ve spent, or one where you’ve worked out how much you’ll need in the future. Maybe you even use some budgeting software. Who knew it was so much fun lining up a bunch of numbers?

After we line up all those numbers, it makes it very easy to come up with spreadsheet answers to our financial questions. But what about the answers that don’t fit on a spreadsheet? I get asked often about this issue. What if the spreadsheet makes it clear we should do one thing, but we’d rather do something else?

I’m facing one of those decisions at the moment. I’ve worked through my tax planning for 2013, and the spreadsheet tells me that I’ll cut my taxes if I add extra funds to my retirement account. I’ve already fully funded my retirement for the year, but being a small-business owner, I have the option to add more.

It will lower my tax bill if I do, but I’m seriously considering not doing it, even though the spreadsheet shows that it makes sense. What’s stopping me? I want that money available for another important goal next year.

I realize that if I follow through with this decision, I’ve determined that it’s worth it to pay the taxes and keep the money available. But in this instance, the numbers on the spreadsheet don’t do a very good job of accounting for my important goal. Yes, it seems as if what I’m suggesting runs contrary to what I’ve said in the past about behaving and following our plans, but stay with me for a minute.

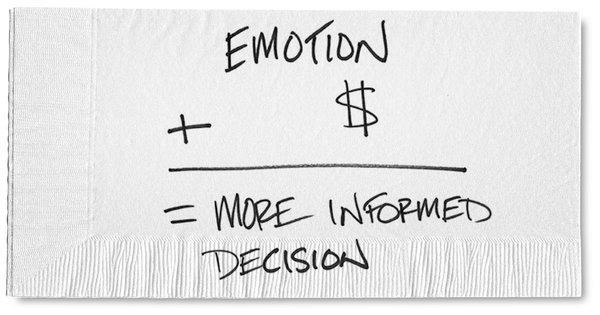

One of the biggest reasons we misbehave is that we react solely to emotion instead of considering the facts. But the opposite is true, too. When we consider only the facts and don’t take the time to understand our emotions, it can lead to regret and make it difficult to behave.

In this instance, my decision takes into account both the facts (I won’t save as much on taxes) and the emotion (but I’ll have the money available for my goal). Yes, it’s not the optimal spreadsheet answer, but I feel as if it’s the right decision for me.

This is a perfect example of what my friend Tim Maurer has said about personal finance. It’s more personal than it is finance. There are certainly other examples of this push and pull between the spreadsheet and what we feel:

■ Hold the latte.

To save money, one of the first things budget experts recommend cutting out is that morning cup of coffee. Of course we can save money by making our own coffee, but what if that perfect cup of coffee made by our favorite barista just makes us feel better? What’s that worth to us?

■ Buy economy.

It’s time for a new car, and the spreadsheet shows that buying a cheaper model makes more sense. But we’ve really been saving to buy our dream car. We have the money to afford the dream, but the spreadsheet says to save that money instead. The numbers may point to economy, but can we handle the emotion of passing on our dream?

■ Don’t stay home.

If we look only at the numbers, it often doesn’t make sense to be a stay-at-home parent. There may even be a financial cost for that decision. But what’s the emotional cost if we’ve decided there’s huge value in being with our children every day?

To be clear, I’m not recommending that we don’t consider the facts in these decisions, but too often we skip over the question of whether we can handle a financial decision emotionally. It’s no wonder that it’s so hard to behave if we pretend that emotion has nothing to do with our decisions. We need to consider our financial decisions through both the filter of numbers and emotions.

For instance, why pretend that we don’t have mixed emotions about saving money? Of course it makes sense to systematically add money to our savings account, but we also wonder about the other things we could do with that money. Recognizing that emotion and putting it in context can help us do a better job of sticking with our plan instead of only looking at a row of numbers on a spreadsheet.

Perhaps I’m in the minority, but I think spreadsheet answers are only the starting point for most of us. They give us a baseline and a way to get closer to our goals, and sometimes we’ll be comfortable with the spreadsheet answer. But when it doesn’t feel right, don’t panic.

Take the time to walk through why another option feels like a better choice and understand the trade-offs of that choice. We can even add a line item to our spreadsheet with the value we place on our option. It can help add some perspective even though that number is based on how we feel.

Sometimes, facts will trump our emotions, and we’ll go with the optimal spreadsheet answer. But sometimes, emotion will win in our financial decisions, and if we understand why, it becomes a decision we can handle without regret.

About the author: For the last 15 years, Carl Richards has been writing and drawing about the relationship between emotion and money to help make investing easier for the average investor. His first book, “Behavior Gap: Simple Ways to Stop Doing Dumb Things With Money,” was published by Penguin/Portfolio in January 2012. Carl is the director of investor education at BAM Advisor Services. His sketches can be found at behaviorgap.com, and he also contributes to the New York Times Bucks Blog and Morningstar Advisor. You can now buy – “The Behavior Gap” by Carl Richard’s at AMAZON.

0 Comments