The following blog is by Carl Richards originally published in The New York Times’ Blog.

We’re really good at telling ourselves stories.

One story I told myself for a long time was that I needed to buy a lot of books. It’s my job to be on top of things, so I’d go to Amazon, read a sentence or two of a review, and buy the book.

Over time, this habit of buying every book didn’t actually lead to reading more of them. Instead, I found myself restacking a tower of books I never read. Once I accepted that my story had a few holes, I adopted a new rule. A book had to sit in my online shopping cart for at least 72 hours before I hit the “buy” button. Since then, the number of books I purchase has dropped significantly.

It’s definitely helped having this rule, but even the best rules are easy to break and I fully expect to return to my old book-buying ways soon enough. Right around the time you find the perfect way to force yourself to spend less, something changes and you fall back into your old habits. So you look for a new system or a new phone app, convinced that if you just find the right one, you’ll finally fix this behavior.

If you think I’m exaggerating, take a look at the market for productivity tools. There are more apps than ever before, but we still struggle to accomplish tasks.

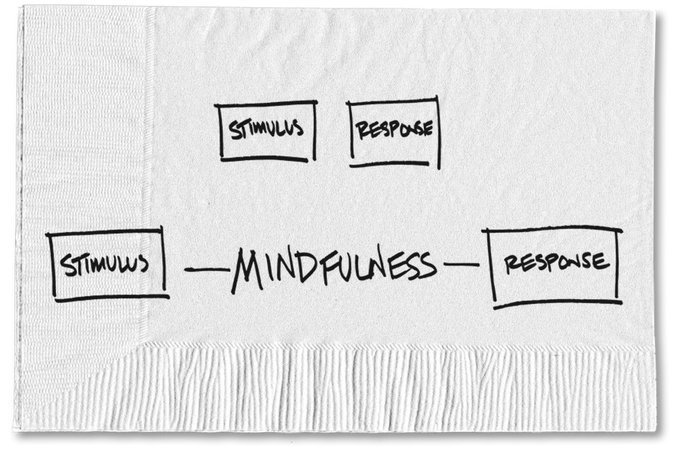

So if solutions tend not to come from tools, what’s really happening in our heads? Why is there a gap between all this great intention and our behavior? I suspect it’s because, in part, of how fast we now respond to stimulus. In our modern world, we’ve been trained to respond to things immediately.

Just think about how hard it is to avoid checking your email when you hear the familiar ding. Some of us even suffer from phantom phone vibration. We’re so attuned to these signals that we will respond to them even when they haven’t really happened. So is it truly a surprise that we allow ourselves no time to think or reflect before we react?

So what if instead of just acting (or reacting) we stopped, took a deep breath, and checked how we’re feeling at that moment?

The word that researchers like Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn have used to describe this idea is “mindfulness.” In an interview with The Harvard Business Review, another researcher named Ellen Langer, who has spent nearly four decades studying the topic, describes mindfulness as “the process of actively noticing new things.” She goes on to suggest that “when you’re mindful, rules, routines, and goals guide you; they don’t govern you.”

So what does mindfulness look like? Let’s say, for example, you have a weak spot when it comes to mountain biking and habitually overspend on gear. To fix it, you set a budget and have a phone app that tells you when you’ve reached the limit. You’re all set, right?

But the next time you go to the bike shop, all your good intentions go out the window. Budget blown. Spouse mad. Go on to repeat this process over and over.

So then you decide you’ll never go to the bike shop again. It works great until Google magically delivers the perfect banner ad while you’re reading an article on how to manage your spending. One click and your good intentions disappear. Budget blown. Spouse mad.

Your behavior is outrunning the rules again. But what happens if you take Ms. Langer’s advice? What if you notice how you feel, focus on thinking less and listening more and avoid judging how you feel? That’s it. It takes only a matter of seconds to check in, and those seconds can have a big impact.

This process came to mind when I read Dan Harris’s recent book, “10% Happier.” Mr. Harris shared how a panic attack on national television, combined with a story assignment, eventually led him to change his approach to handling stress. Now, instead of self-medicating, he relies on meditation and other brain exercises to help him focus. In other words, he found a way to put some space and awareness between stimuli and his response. And, as his book title notes, it has made him 10 percent happier.

A recent study by Tobias Teichert and Jack Grinband discovered that “postponing the onset of the decision process by as little as 50 to 100 milliseconds enables the brain to focus attention on the most relevant information and block out irrelevant distractors.” By focusing on what’s happening right now, you can notice something new. Even if your response is something simple — like, “Wow. Isn’t it interesting I feel this way?” — you’re putting yourself in the moment and creating the opportunity to be guided instead of governed.

This will take time. Like compound interest in the financial world, it’s kind of boring in the beginning because the benefit seems so small. Over time, however, the payback grows, and suddenly it’s very exciting.

You can practice by checking in even after you buy something. A week later, how does it feel? Have your feelings changed? Again, it isn’t about judgment, but giving yourself a point of reference.

If you want something more proactive, try something similar to Jim Collins’s experiment. The “Good to Great” author wanted to figure out what he really enjoyed. So he bought a new lab notebook, put his name at the front, and decided to study himself closely, like a scientist watching a bug. Each night Mr. Collins wrote down the answer to this question: When during the day did I feel bored; when did I feel engaged?

Remember, your primary goal is just to notice. It takes time to get used to the idea of not following a checklist or a 10-step plan, but that’s the point. Being mindful is about being, not necessarily doing.

About the author: For the last 15 years, Carl Richards has been writing and drawing about the relationship between emotion and money to help make investing easier for the average investor. His first book, “Behavior Gap: Simple Ways to Stop Doing Dumb Things With Money,” was published by Penguin/Portfolio in January 2012. Carl is the director of investor education at BAM Advisor Services. His sketches can be found at behaviorgap.com, and he also contributes to the New York Times Bucks Blog and Morningstar Advisor. You can now buy – “The Behavior Gap” by Carl Richard’s at AMAZON.

0 Comments