The following blog is by Carl Richards originally published in The New York Times’ Blog.

On a recent business trip, I got to stay at one of the nicest hotels I’d ever seen. The staff was incredible, and the room was amazing. My first morning there, I needed to grab some breakfast.

I normally skip hotel restaurants because I know they can be kind of expensive, but I was tight on time. So when I walked in and saw how great the buffet looked, I jumped in line. I expected the buffet to cost more than a regular breakfast, but I was hungry and in a hurry. Those two facts helped me decide it was worth it, but I was also determined to make every dollar count.

I ate just about one of everything from the buffet. It ended up being way more food than I normally eat at breakfast. When I went to pay, though, I got a surprise. My server asked for my room number, and after checking, she informed me that the meal was included in my stay.

I immediately thought, “If I’d known that, I’d have eaten less.” The next day, knowing that the breakfast buffet was included with my room, I ate my normal amount of food.

Now, you could say I have an eating disorder, but in reality, it was about money. When I thought I was paying for the meal separately, I wanted to get the best value possible. But once I knew that breakfast was covered, it became something I’d already accounted for in my head. It wasn’t something extra.

I doubt I’m the only one guilty of stuffing myself silly at a buffet. But it’s a prime example of what we do when there isn’t a clear relationship between what we’re getting and what we’re paying. It also crops up when we aren’t clear about why we’re spending money in the first place.

If we leave anything unclaimed, we think we’re missing an opportunity. For instance, think about “buy one get one” offers. Yes, we get a good deal. But what if we really didn’t need the item in the first place? We now have two things we didn’t need. Like eating at the buffet, we’re focused on the idea of maximizing our money when, in reality, we should have been focused on getting what we actually needed.

My body didn’t need plate after plate of food, but my brain couldn’t separate perception from reality. It’s a financial trick we play on ourselves all the time. We convince ourselves that we’re really getting our money’s worth, but the results don’t necessarily match our needs. And as we get out of balance, it’s no wonder that it becomes more difficult to feel good about our money decisions.

To be clear, there’s nothing wrong with buffets or discounts, but gorging on food or cashing in on every coupon does not make us smart about money. What does make us smart is taking the time to figure out what we really want or need and then acting accordingly.

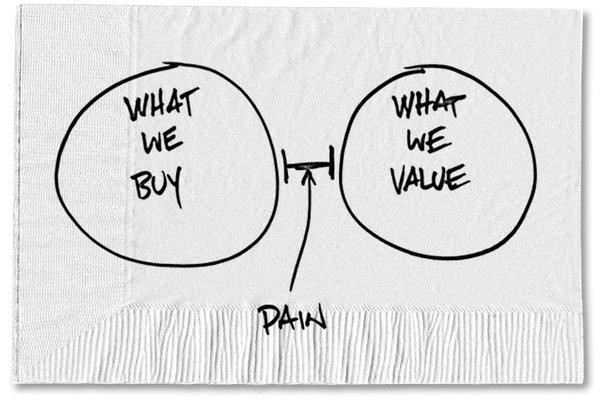

It seems to me we get into the most trouble when we separate our buying decisions from what we say we value. What if instead of focusing solely on the price tag we focus on how what we’re buying fits into our lives?

It may seem like a small thing, but it can help us gain a better perspective. For instance, on my first time through the buffet, I equated price with quantity. It wasn’t about actually enjoying breakfast. The next day, however, I knew the buffet was just one piece of my overall stay. It changed my perspective, and I ate my regular amount of breakfast and enjoyed every bite. I knew where the buffet fit.

Knowing how a money decision fits won’t always be this straightforward. There will be conflicting signals, particularly when we face the temptation of, “Act now. This deal will never happen again.” That’s rarely the right reason to hit the buy button.

By making decisions based on both price and fit, it becomes a bit easier to weigh the value of what we’re doing. It also becomes less likely that we’ll look back with regret or end up with heartburn, two things I suspect we’re all eager to avoid.

About the author: For the last 15 years, Carl Richards has been writing and drawing about the relationship between emotion and money to help make investing easier for the average investor. His first book, “Behavior Gap: Simple Ways to Stop Doing Dumb Things With Money,” was published by Penguin/Portfolio in January 2012. Carl is the director of investor education at BAM Advisor Services. His sketches can be found at behaviorgap.com, and he also contributes to the New York Times Bucks Blog and Morningstar Advisor. You can now buy – “The Behavior Gap” by Carl Richard’s at AMAZON.

0 Comments